Choral Considerations for the Transgender Singer

When it comes to choral singing, there are many different aspects that a director needs to take into consideration while working with a transgender singer. Granted, as every situation is contextual and every transperson is different, the impact of these considerations will vary from person to person and situation to situation. It’s important to be familiar with all of these though so you are best prepared to not only understand potential circumstances you may run into, but also how to best support your transgender singer.

The following sections are going to be broken down for easy perusal and quick access when looking at different considerations. In these sections, I will focus on, voicing/sections and standing arrangements, the effects of hormone therapy on the voice, potential alterations of gender expression made by trans people that could affect vocal pedagogy, such as adjusting the speaking pitch, or the effect of binders and waist trainers on the singing voice, and discuss a few singing strategies for the transgender singer.

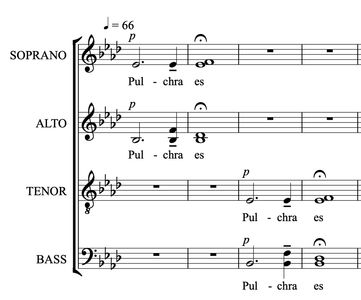

Voicing, Sections, and Standing Arrangements:

Some of the most common questions asked about working with transgender singers in the choir revolve around what voice part a student should sing, what section they should stand in, and how a choir director should arrange their singers. Most times, the question is asked innocently and with good intentions, typically by a choir director attempting to produce the best choral sound without hyper-focusing on the transgender student.

Though the question seems like a static consideration, the answer is dynamic and contextual. It depends on the singer, their comfort level, and a vast majority of other concerns. The first step of this process is to remove the gendering entirely from the vocal instrument before you even begin voicing.

“I have a variety of genders in every voice part, so as a conductor I simply refer to my singers by voice (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) rather than by gender (men, woman, boys, girls, ladies, gentlemen. I also ask any guest conductor or clinician working with my chorus to also refer to voice parts rather than genders.” (Miller, 62)

“I’m not too sure how I feel about this new choir director. I observe him as he walks in, suddenly anxious about what he might say today to make me feel uncomfortable. 'Good afternoon Ladies and Gentlemen. Let’s split up into sections to work on the Bach. Women, stay in here and men, go to Room 114.' I’m frozen in my seat as everybody else begins to move. This year, I am finally living full-time as a female, but I still sing Bass II in the choir. Where do I go? A quick look at my outfit would have me remaining in the room. A bright pink shirt with a white bra strap peeking out, paired with black capris and a simple pair of ballet flats declare to the world that I’m a woman. I look up and the majority of the tenors and basses have already left the room. I begrudgingly stand and make my way to the door. Each step away from the other women in the ensemble highlights how different I am. As the door to the main choir room closes, I see the director moving on, completely oblivious as to how he just made me feel. These are the times when I hate choir.” (Bartolome & Stanford, 126)

This goes for the names of ensembles as well. There is no need to use "Men's Choir" or "Women's Choir", when "Treble Choir" or "Tenor/Bass Choir" or something else more creative can be used. By referring to the voice part rather than the gender, you instantly help the trans singer focus on their voice and not their gender. When beginning the voicing process, use gender neutral words like “singing high or low” or “lighter versus darker”. Vocalize the student as normal and find their healthiest singing range and determine where you would place that student ordinarily if they were cisgender.

Once the student is vocalized, privately discuss what section you think would be best suited for their voice. For some trans singers, that will be that. They could happily go off into the section and not have any complaints because that’s where their voice fits best. For other trans singers, the issue will be more complex. No matter the language that we use, soprano and altos are stereotypically considered “the girls”, while tenors and basses are “the boys”. That connotation is longstanding and will not be able to be erased.

Because of this, some trans singers are going to feel uncomfortable being in a section that has a gendered connotation. There are a few different ways to approach this discomfort with the student. Firstly, the student should be reassured that it is okay to be uncomfortable at the prospect of singing in the particular section. Note that this goes beyond the preponderance of a student saying they “don’t like” something or don’t want to sit in a section because their friends are not nearby. Being in the wrong section could heavily trigger gender dysphoria and cause instant animosity towards choir and the director of the choir. This has the potential to cause the transgender singer to give up choir or singing in general.

Secondly, talk with the student and have an honest conversation about the vocal benefits of singing in the section that their voice fits best into. Don’t push the student one way or the other, as that could end up making the student feel more uncomfortable, look at it as a way to give the student all the information before making the choice that’s best for them. Singing in a different section could mean the voice is more fatigued or the vocal quality might not be as strong as the other members of the section, and they might not be able to hit 100% of the notes.

From there, if the trans student still would be more comfortable in another voice part, choose one that they could be more comfortable in and find the most success in. For example, a tenor or bass/baritone with a strong head voice/falsetto could fit into an Alto section. Depending on the range, Alto I might be more suitable as the Alto II part could venture too deeply into their passagio, and the higher notes of Alto I might not reach the upper limits of the student’s range.

For a soprano/alto, shifting some students to Tenor I is a technique that is used for cisgender singers all of the time, especially when there is a lack of tenors (which frequently seems to be the case). Work on strengthening the chest voice of the student to assist them in reaching those notes. See the “Singing Strategies for the Transgender Singer” section below for more specificity. If a student is completely unable to sing in another part due to range or other vocal issues, that might be an instance where the singer needs to sing in the original voice part, but the director will need to take great care to avoid gendered language or potential gender dysphoria triggers.

Once sections are determined, it’s extremely important to figure out a good standing arrangement. The wrong standing arrangement can publicly out a transgender student, make them extremely uncomfortable, and draw public attention to the singer.

“While the director reluctantly agreed to let Mel wear a dress for the concert season, the SATB choral formation he selected caused a measure of anxiety for Mel during performances:

‘And so there I was, on the far end of the basses, the only person in a dress. And so I wasn’t really happy with that. In the winter concert, we did a processional and it was girls on one side and guys on one side. I had to be with the guys because I was standing on the guys’ side. That put me in kind of an awkward situation because it was possible that somebody could hear, ‘Oh my gosh, that girl is not singing soprano or alto. She’s a bass. So maybe she’s not a she.’ It was very awkward.’” (Bartolome, 37)

By simply altering the standing arrangement, the director in the aforementioned example could easily have prevented this experience. The “perfect” standing arrangement is not going to exist that suits the needs of every choir. Directors can be creative in how they change their standing arrangements.

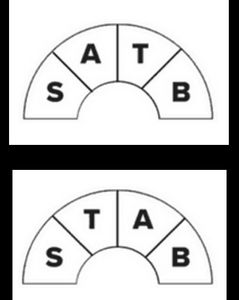

For example, if a trans student is in the Soprano section wearing a tuxedo as their uniform, consider using a Soprano Tenor Alto Bass (STAB) formation, in which the trans student stands next to a tenor. The goal is to minimize as much attention being called upon the trans singer as possible. Let them feel comfortable and blend into the ensemble, just like any other singer.

Main Take-Aways:

· Avoid gendered language in rehearsals and when discussing voices.

Avoid naming choirs with gendered language such as "Men's Choir" or "Women's Choir". Use Treble Choir, Tenor/Bass Choir, or something else creative.

· Student comfort level is paramount, triggering gender dysphoria is not worth it for a slightly better sound.

· Attempt to set the student up for success if singing in a different voice part. It is probably easier for a bass to sing Alto I than Soprano I.

· Be mindful of uniforms in standing arrangements. If a student is standing alone, wearing a dress in the middle of a group of tuxes, they can instantly be publicly outed.

· Change your standing arrangements so that trans students can easily blend in and don’t have unneeded attention brought on them.

· Recognize that just like cisgender singers, trans singers’ voices are extremely personal to them. Some may be dysphoric just from their voice alone. Maintain a warm, friendly, and relaxed demeanor to make the student comfortable.

· Respect the student and communicate that respect during this process.

Effects of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) on the Voice:

Typically, instead of being prescribed hormones, trans people who are under the legal age of consent will take puberty blockers, also known as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, which effectively press pause on puberty. While there are other physical changes, the only vocal effect is the prevention of the voice change/lowering in those assigned male at birth. When puberty blockers are discontinued without any other hormones added, puberty will resume as normal. (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2019).

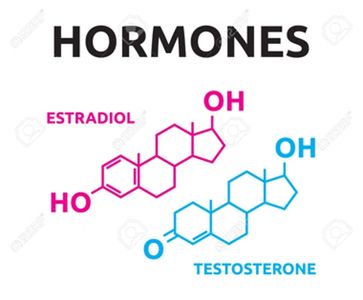

While it is unlikely that a student in middle school or possibly high school will be prescribed hormones as a minor, it is not unheard of. The effects of hormones are vastly different. For MtF individuals, those transitioning from male to female, who are wanting to take hormones, estrogen and anti-androgen are typically prescribed. In some cases, progesterone will be prescribed. Regardless of the hormones prescribed and being taken by MtF individuals, “once the voice has gone through a male adolescence, no hormone therapy will reverse this process.” (Sims, 374)

If an MtF person wishes to feminize their voice, they will need to do so with manual manipulation and training. “Often a speech therapist will be needed because fundamental frequency and resonance changes will likely be necessary.”(Sims, 374)

For FtM individuals, those transitioning from female to male, who are wanting to take hormones, testosterone is prescribed and administered via injection. The effects of testosterone on the voice can be swift. For an aural and visual example, check out this video of a transman going through 4 ½ years of testosterone therapy in 1 minute. Listen carefully to the vocal differences: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-py2WIOp2q8

Dr. Loraine Sims, a former professor of mine at LSU, published a case study about Lucas. Lucas was a trans-identifying student who began testosterone therapy while Dr. Sims instructed him in vocal lessons, collecting data, and having him scoped to document vocal fold changes in video format. Before testosterone therapy began, Lucas’s voice type was best described as a soprano. The following is general overview of some of her results:

6 Weeks On T:

“[The] lesson began with Lucas saying that he was frustrated with his voice. He reported that he felt as though it hard to produce a clear tone. What happened in the initial exercise was that it appeared to be mixing stronger in the primo passagio than previously...For the first time, the voice dropped all the way to C3 in the chest voice. This range was a minor third lower than any previous lesson.” (Sims, 369)

5 Months On T:

By month 5, Lucas began warming up in the tenor range with falsetto production “very weak.” Getting lower in the range, “the timbre of these notes was a bit stronger than typical falsetto, but still not like the usual mezzo soprano mix in that range. We had to police the larynx so that he did not simply raise the larynx rather than allow the voice to turn over as he reached the upper limit. In this way, it was similar to training all young tenors.” (Sims, 371)

1 Year On T:

“After a year, the singing voice was trained like any tenor. Minor acoustic adjustments were needed due to higher than average formant frequencies. If an FtM trans singer had a lower range before testosterone, you might expect the result to be a baritone.” (Sims, 373)

2 Years on T:

“The quality and range changes owing to testosterone treatment were that the chest voice range increased and the soprano range was drastically diminished. Falsetto/head production was unavailable for a while, but became a viable option in limited range. Tenor production continued to be the preferred timbre for two years.” (Sims, 373)

2 ½ Years on T:

“After two and a half years, Lucas also has access to a lovely countertenor.” (Sims, 373).

This case study was one particular individual. Just like with every singer, the voice change is going to be unique to that person. In my times teaching private voice to a transman in his mid 30’s, undergoing the first year of testosterone therapy, I couldn’t help but note how similar the experiences he was going through (ex: voice cracks, lack of falsetto, random breathiness and loss of sound/control) were similar to those experienced by the middle school tenors and baritones I had worked with.

Main Take-Aways:

· Puberty blockers will simply pause puberty for those students who are placed on them.

· Estrogen/Anti-Androgen will not undo the male puberty process on the voice of MtF individuals.

· Testosterone treatments can quickly affect the voice, lengthening the vocal folds, and causing similar issues to adolescent tenors/baritones including a lowering of the speaking/singing pitch, voice cracks, unavailable falsetto/head voice production, and an increased chest range with a lowered head voice range.

· HRT is not a decision that trans people take lightly. For many trans people, any medical step taken is very personal and they are not required to share it with you. You can always give the option in a friendly way: “If you want, let me know if you start taking hormones, because your voice can do some funky things and I can help you navigate that!”, but do not pressure the singer. While knowing the information can help you, medical information, at the end of the day, is private.

Alterations of Gender Expression that Can Affect Vocal Pedagogy:

Gender expression is an important facet for transgender people. By altering what they wear, how they speak, how they walk, etc. they are better able to present the gender they feel most comfortable with. For many, even small changes can be the difference between feeling good or bad about themselves.

Sometimes, these alterations of gender expression can have an adverse effect on vocal pedagogy or the singing process without realization by the teacher and sometimes even the student. These alterations can be external, stemming from clothing or worn items, to internal, stemming from purposeful alterations to one’s usage of the body.

One of the most common forms of internal alterations of gender expression comes from altering the pitch of one’s voice. This can be a critical aspect in a trans person’s life, as some may desire to speak with a higher, more “feminine” pitch, while others may desire to speak lower with a more “masculine” pitch. These pitch alterations, especially when done unhealthily or without speech therapy or an understanding of the vocal mechanism, can cause issues like laryngeal fatigue and increased tension in the voice. These can obviously lead to vocal issues for speaking or singing and may prevent the singer from doing either.

I highly recommend that teachers work with their transgender singers individually to assist in teaching laryngeal relaxation exercises. A great strategy is having them find a private area that is soundproofed or dampened, like the inside of a practice room, or a car while at home, and let them relax the larynx into a relaxed position. Letting students alleviate that laryngeal fatigue will help them preserve their voice and give it time to rest. Drinking lots of water and giving periods of vocal rest—no talking or singing will also help.

External gender expression alterations relate mostly to what a trans singer is wearing. These alterations can alter the body to accentuate or deemphasize parts of the body. For example, “Breasts are of particular importance to transgender individuals because they are viewed as an external indicator of gender...Individuals in the transgender population often change their breast anatomy and physiology to achieve an aesthetic more congruent with their gender identity.” (Maynock & Kennedy, 75) Those who identify as FTM or transmasculine commonly alter their expression via binding to minimize the appearance of breast tissue to appear more masculine. Binding can be accomplished in numerous ways. Some people use ACE wrap bandages, tape, or other material. Others will purchase or make their own “binders.”

Due to its nature of altering the shape of the body, binding has potential health outcomes that can affect singing. Individuals who bind have reported many health outcomes of binding that can ultimately affect their singing ability including pain (chest, shoulder, back, abdominal), respiratory (cough, respiratory infections, shortness of breath), musculoskeletal (bad posture, rib or spine changes, rib fractures, shoulder joint ‘popping’, muscle wasting) neurological (numbness, headache, lightheadedness or dizziness), gastrointestinal (digestive issues, heartburn), general (fatigue, overheating, weakness) or some kind of skin/tissue issues. (Peitzmeier, Gardner, Weinand, Corbet, & Acevedo, 71, Table 3)

All of these specific health outcomes can also negatively affect singing, especially when looking at elements of posture and breath. These are all things your trans singer might struggle with due to their binder. That’s not to say that there are not positive outcomes to a binder.

“Although binding is associated with many negative physical health outcomes, it is also associated with significant improvements in mood and mental health. In response to open-ended questions about mental health effects and motivations for binding, participants consistently affirmed that the advantages of binding outweighed the negative physical effects. Many participants said that binding made them feel less anxious, reduced dysphoria-related depression and suicidality, improved overall emotional wellbeing and enabled them to safely go out in public with confidence.” (Peitzmeier et. al, 73)

Transgender individuals should ideally work with a medical provider while binding and familiarize themselves with the risks and potential negative outcomes in addition to the positive. While medical advice should be strictly given by healthcare professionals, some doctors have stated that it is possible to “reduce negative outcomes associated with binding by recommending ‘off-days’ from binding when possible, avoiding elastic bandages, duct tape and plastic wrap as methods for binding and using caution with commercial bindings.” (Peitzmeier et. al, 74) This advice may temporarily assist with alleviating discomfort until a trans singer can see their healthcare provider.

It should also be noted that just as you would probably not ask a cisgender person about their underwear, asking about a trans person’s binder can be seen as an invasion of privacy. Have the necessary information on standby for both you and your trans student who may be using a binder.

Corsets and waist trainers are similar to binders, but while binders are worn on the upper chest, waist trainers are worn down on the lower to midsection of the abdomen. “The biggest difference between corsets and waist trainers are the materials used. Waist Trainers have breathable fabrics such as nylon and spandex with flexible spiral plastic boning while corsets have rigid, unbreathable materials such as leather with inflexible steel boning and tight lacing. Another difference is that some waist trainers do not go up the torso as high as a corset.” (Inselman, 2018)

These garments, while likely less prevalent than binders, are sometimes worn by transfeminine individuals who wish to feminize the waist shape, creating curves in their body. Though more research is required on the effects of corsets and waist training on singing, it should be noted that aggressively wearing a corset or waist trainer, can cause organ redistribution, shifting of bones, back pain, respiratory difficulties, and digestive issues.

If a trans individual makes the decision to wear a corset or waist trainer, it is crucial to find the correct size, wear it for limited spaces of time, and perform stretches and deep breathing after removal. (Inselman, 2018)

Main Take-Aways:

· There are many different ways that singers can alter their gender expression, some more subtle than others.

· Transgender singers may manually alter their speaking and singing pitch to sound more masculine or feminine, which can cause laryngeal fatigue.

· Binders are typically worn by transmasculine individuals, or by those who wish to reduce the appearance of breasts.

· Binders can have health outcomes that can negatively affect singing in different ways, but provide many positive mental health outcomes.

· Trans people ideally should seek medical advice from a healthcare professional when it comes to binding. There are resources online, but a knowledgeable healthcare professional is best.

· Having days where the binder is not worn can provide some relief for trans singers experiencing negative effects.

· Corsets and waist trainers can negatively affect one’s health and singing, especially when worn for too long, or the incorrect size is used.

· It is imperative for trans singers that wear a corset limit their time spent wearing it and perform stretches and deep breathing after removal.

Singing Strategies for the Transgender Singer

As the transgender singer navigates their singing journey, sometimes different factors come into play that can affect their singing. Maybe it’s the laryngeal fatigue that comes with speaking or singing at a higher or lower pitch than what would be “standard”. Perhaps the singer is emulating a model that is resulting in an undesired vocal tone or creates a sound that is lacking resonance. Ideally, we will use the vocal pedagogy that we know to be best, aiming for the singer to have a clear, healthy, and resonant tone with proper breath support that is free of restraint.

Many of these aspects are completely achievable with the transgender singer. A singer will be able to use a good “singer’s posture” or have a lovely clear tone, or use proper breath support, but certain considerations need to be made. For example, if a singer is wearing a binder or waist trainer, there is a chance that their posture or respiratory function will be negatively impacted. (Peitzmeier et. al, 71)

One can still teach the singer to take a low, proper breath or stand with good posture, but just understand that the maximum breath capacity or “best posture” might be slightly limited due to the binder or waist trainer. I recommend striving to attain that best posture and breath as possible, as long as it remains comfortable to the student. Singing with binders and waist trainers is an area that requires more research to fully understand their impact.

A common issue trans singers face is laryngeal fatigue. By changing the way they speak or sing, singers can add tension or exhaust the vocal folds.

“Melanie also began to experiment with her speaking voice, cultivating what she considered a more feminine sound and inflection. She told me, ‘I talk a lot with a higher larynx. I tend to do that just to be more ‘passable’, for people not to recognize. It has actually caused some vocal issues for my own singing, but if I bring my voice down back to its natural resonance, people will perceive me as being male.” (Bartolome and Stanford, 126)

Singers can relieve the tension by using different laryngeal relaxation exercise. A yawn sigh into the chest voice can help, as can a return to speaking in the most “natural” speaking voice. Other techniques for laryngeal relaxation include using semi-occluded vocal exercises (v’s or other voiced consonants, lip trills, humming, etc. especially on descending lines. A great exercise is vocalizing with a straw. For an example of this, see Ingo Titze explain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0xYDvwvmBIM

I also recommend using any range extending exercises that can help strengthen the “outer edges” of the voice. For those assigned male at birth, work on developing the falsetto register to be clear and strong. It is a good idea to use exercises that can strengthen the passaggio. For those assigned female at birth, work to strengthen and develop the chest voice. If they are undergoing testosterone therapy, understand that the voice is going to rapidly shift and develop, similar to an adolescent male. Also, remember that a higher pitch does not mean a forgoing of resonance. As the singer continues to grow and develop the voice, try and work to find healthy ways of finding resonance in the sound.

Main Take-Aways:

· Continue to work towards a healthy vocal production while helping the singer achieve a range that can work for both your and their needs.

· Enforce elements of good singing technique and make minor adjustments as needed for the singer’s comfort depending on if they are wearing a binder or waist trainer. More research needs to be done in this area.

· Familiarize yourself with laryngeal relaxation exercises that can help a trans singer relieve tension in the voice.

· Vocal rest and drinking water are great ways to help the singer recover.

· Work the outside ranges of the voice, specifically strengthening the falsetto and chest voice.

· Just changing the pitch does not mean the work is done. Find ways to increase resonance in your singer in a healthy way. More research needs to be done in this area.

A Small Blurb About Programming Choral Music:

When selecting your choral music, be mindful of programming. Select literature from composers of various identities and backgrounds. Seek out pieces that you wouldn’t “ordinarily do”. Be mindful of the text and subject matter of the piece. How will this relate to your LGBTQ+ students? How will it relate to your students of color? How will it relate to your students of various religions? Keep these things in mind as you approach concert seasons. Find ways to showcase music from people of all walks of life, your students will thank you for it.

Copyright © 2024 Blurring the Binary - All Rights Reserved.